Development on Kangaroo Island: The Controversy Over Southern Ocean Lodge

Dr. Freya Higgins-Desbiolles

School of Management

University of South Australia

GPO Box 2471, Adelaide, SA 5001

Tel: +61 8 8302 0878/ Fax: +61 8 8302 0512

email: FreyaDOTHigginsDesbiollesATunisaDOTeduDOTau

Used by permission of the Publishers from ‘Development on Kangaroo Island: the controversy over Southern Ocean Lodge’, in Stories of Practice: Tourism Policy and Planning ed. Dianne Dredge and John Jenkins (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011). Copyright © 2011

A list of acronyms can be found at the end of the document.

Southern Ocean Lodge: Controversial Development on Kangaroo Island

Introduction

This case study explores the policy context and planning approval process for the Southern Ocean Lodge (SOL) resort development on Kangaroo Island (KI) in the 2000s. SOL has described itself as ‘Australia’s first true luxury wilderness lodge, promoting exciting new standards in Australian experiential travel’ (brochure ‘company profile’). Despite these lofty ambitions, this development sparked major controversy in the KI community, was opposed by the KI Council and was approved under the South Australian state government’s major developments process. The analysis of these events offers interesting insights into the planning approval processes for tourism developments in communities concerned with controlling their future and protecting valued environments.

Kangaroo Island is an iconic tourism resource for both the state and the nation. Its natural beauty and abundant wildlife attract tourists from Australia and the world. The Kangaroo Island community is aware of its unique environment and actively pressed for the sustainable development of tourism in line with community needs and goals. As a result, the Tourism Optimisation Management Model (TOMM) was developed, which represents ‘a unique example of a “community”-driven, visitor management system’ (Jack n.d.).

However, despite having such a unique community-driven approach to tourism planning, KI has seen its fair share of development conflicts. More recently, a development proposed for Hanson Bay on the western end of KI, SOL, generated significant controversy and opposition. As a result, the planning approval process was shifted from local government to the South Australian state government. This report analyses the dynamics of the conflict and employs a social construction approach to explain how events occurred as they did.

Methodology

This project evolved from an observation of tourism development dynamics on Kangaroo Island. This empirical case study, focused on micro-level events, is meant to shed light on macro-level dynamics. As Yin claimed, ‘a case study is an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident’ (1994: 13). Tourism planning is best understood by examining real-life experiences grounded in detailed accounts of contexts.

Yin also advocated sound case study methodology to avoid criticism of it being ‘soft research’ prone to researcher bias and sloppy technique (1994: 9–13). This project used sound case study technique to corroborate narratives and triangulate the data by reviewing documentary evidence, interviews and using a reflexive research technique. Primary documents include: government policies and plans; development application materials; public, government agency and non-government agency submissions to the planning approval process; government documents obtained through freedom of information requests and letters to the editor written when the development proposal was under consideration. In 2009 more than 25 focused interviews were conducted with stakeholders, including the developer, community members both in favour of the development and against it, representatives of government agencies that contributed to the planning approval process, former members of KI Council, politicians, KI tourism operators, environmentalists and experts who participated in these events. It must be mentioned that the KI Council prohibited interviewing of any of its current staff and councillors, claiming that the people sought for interview had had ‘very little to do with the decisions on this matter. It was a major project status and hence was not ultimately Council’s decision’ (email communication from Carmel Noon, CEO of KI Council 17 February 2009). Former members of KI Council have disputed this interpretation, thereby indicating the political sensitivity of this research project.

This chapter offers a narration of events which shed light on the tensions and dynamics of contemporary tourism development in an era of pro-growth dynamics set in a context of increasing awareness of human impacts on the natural environment.

Background

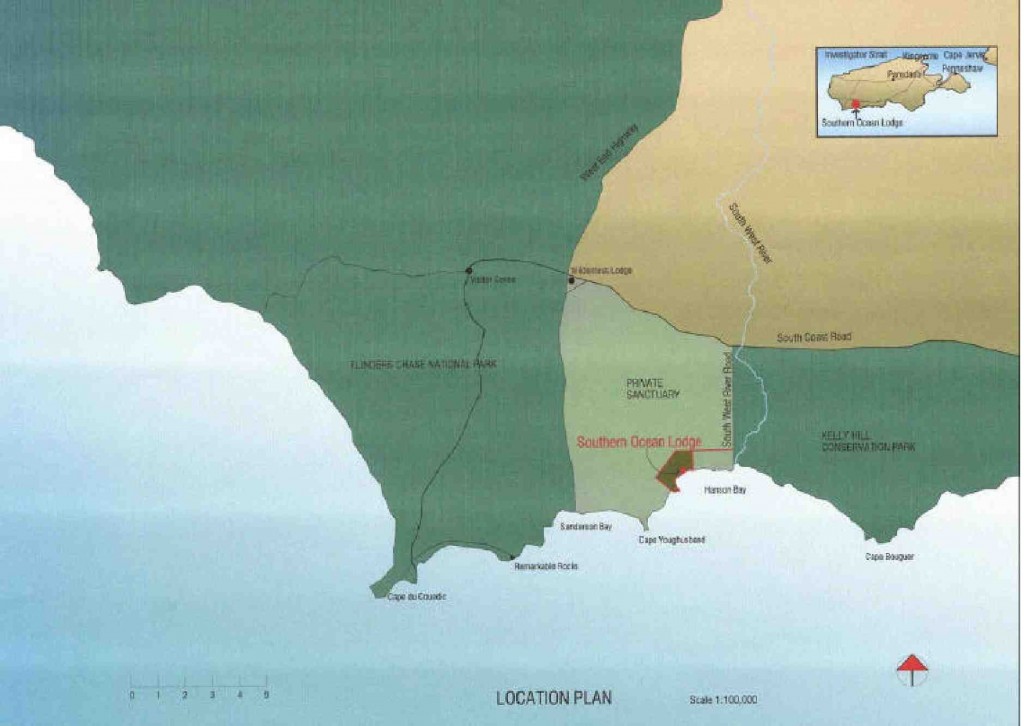

Kangaroo Island lies off the mainland of South Australia. It is 155 kilometres long and up to 55 kilometres wide (Figure 1) and retains almost 50 percent of its original native vegetation, half of which is protected in national and conservation parks. The permanent population consists of some 4,400 people; with a significant and increasing number of non-resident landowners. In 2003, 150,915 people visited KI, 26% of whom were international visitors (source Jack & Duka, n. d.). The current visitor to resident ratio is approximately 40 to 1 (Toni Duka pers. comm. 16 September 2008).

KI diversified into tourism following the 1989–90 crash in wool prices. The development of tourism occurred when the island’s agricultural sector was declining and there was concern about retaining young people in the community. Nowadays KI is a tourist icon due to its wildlife and its natural environment. Following the introduction of a fast ferry service to KI in 1994, the number of day trippers to KI has increased. These developments and the subsequent rise in visitor numbers concerned both the community and planners. As Miller and Twining-Ward stated:

It became evident that without clear observation and understanding of the motivations and changes brought about by the tourism industry, visitor impacts both on the environment and community, coupled with economic worries and emigrations of youth could easily take their toll on the future sustainability of the island (2005: 203).

In the mid 1990s, following the development of a Tourism Policy and Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy for KI, KI planners developed their own ‘broader and more integrated’ tourism planning tool which became known as the TOMM (Miller and Twining-Ward 2005: 204). The designers of the TOMM opted for establishing parameters of ‘optimal uses’ of resources (Jack n.d.). Proponents of the TOMM argue that it sets out optimal conditions which ‘cover the broad spectrum of the economic, market opportunity, ecological, experiential and socio-cultural factors and as such, reflect the entire tourism system, and so [stands in contrast to other models]… which focus on one specific aspect of a tourism system [the ecological]’ (Jack n.d.).

TOMM surveys provide one particularly helpful indicator of the local community’s relationship to tourism development on KI. This is the measurement criterion in the socio-cultural section that gauges how much ‘residents feel they can influence tourism related decisions’ with the optimal range set at 70 to 100% of residents responding positively. In 2000–01 and 2001–02 only 39% of respondents responded positively. The next census in 2004–05 had only 55.8% responding positively (Duka 2005: 14).[1] Analysis of the data led Duka to suggest that:

Kangaroo Island residents are less likely to accept some environmental cost in exchange for economic and population growth on the Island, that most do not feel that they have sufficient opportunity to have input into local tourism related decisions and that tourism development is not fully occurring in line with community values for the Island (2005: 21).[2]

It is clearly difficult to meet the needs of all stakeholders in tourism. Conflicts and tensions are natural where demands for economic growth clash with a finite environment and communities with diverse social needs. In particular, it is easy to see how communities might resist the growth of tourism in the interest of community wellbeing, whereas the tourism industry and its proponents encourage the growth of tourism. An examination of the controversy that erupted over the proposed development of SOL in 2005 in KI’s coastal landscape zone on the southwest of the island is a helpful case study of such dynamics.

The Proposed Development

The backdrop for the proposed development was James Baillie’s visit to KI in the late 1990s when he was Managing Director of P & O Resorts. ‘The SA Government wanted a “Silky Oak Lodge” on Kangaroo Island, which was one of our properties in North Queensland at the time and they invited us down and to have a look around’ (Baillie pers. comm. 29 May 2009). The places he was shown were mainly farming properties on the north coast of the island which lacked ‘the wow factor’ he considered as essential:

If you’re trying to encourage people to come to a destination, they need to stay somewhere that has the wow factor because that’s the only way you can make the development sustainable. You have to be able to charge [premium] prices and to maintain a certain yield and that’s the only way you can make a development sustainable (James Baillie pers. comm. 29 May 2009).

However, nothing materialised from these overtures. P & O sold its resorts, Baillie left the company in 2001, bought some of the former P & O resort portfolio and started his own company, Baillie Lodges, with his wife, Hayley, daughter of well-known entrepreneur Dick Smith. On another visit to KI in October 2002, the Baillies viewed the Hanson Bay Sanctuary, a 3,485 hectare property of intact bushland. They embarked on a two year process of negotiations with its American owner that resulted in the purchase of 102 ha of the sanctuary. They planned to add this property to their ‘portfolio of very special luxury lodges in which we combined two things: my love of design and hotels with Hayley’s love of the environment’ (James Baillie pers. comm. 29 May 2009).[3]

The $10 million development proposal for SOL included 25 accommodation suites and associated facilities including a main lodge, spa retreat and staff village created on one ha of cleared land (Planning SA 2005) (Figure 2). The site was flanked by Flinders Chase National Park to the west and the Kelly Hill Caves Conservation Park and Cape Bouger Wilderness Protection Area to the east (Figure 3). The development area was situated in the Coastal Landscape Zone on the western end of the Island between two conservation zones.

Figure 3: Site map of the proposed Southern Ocean Lodge development (map provided by SOL developer James Baillie)

James and Hayley Baillie were quoted as saying:

Southern Ocean Lodge will become an icon for South Australia and we hope it’s something SA can hang its hat on as a marketing asset the envy of other States. We believe it will increase visitation to Kangaroo Island and tap into a market that has previously been under-utilized, providing enormous benefits to this community (‘Luxury lodge for south coast’ 2004).

The Baillies promoted the development based on their industry credentials: he with his history with P&O Resorts and she as the daughter of Dick Smith with her experience on cruise expeditions. Dick Smith’s ‘backing’ in the venture appears to have been a significant positive in favour of the development (letter from Bill Spurr, CEO of the South Australian Tourism Commission (SATC), to the Minister of Tourism 6 August 2003).[4] Baillie began conversations with both KI Council staff and SATC at this time seeking assistance with infrastructure for this remote area of KI. CEO of the SATC, Bill Spurr, looked favourably on the proposal and KI Council staff were described as ‘generally supportive’ (letter from Bill Spurr to the Minister of Tourism 6 August 2003).

The SOL development proposal was described as being a ‘major new development proposal which would provide a premium nature based tourism experience for Kangaroo Island’ (MDP 2005). Award-winning, locally born architect Max Pritchard was engaged to design the development which he promised would be a ‘model development in South Australia … [with] nothing like it in existence anywhere in the State’ (‘Full steam ahead for $10m “Lodge”’ 2005: 1–2). It was originally estimated that the development would represent a capital investment of $10 million and once in operation would sustain 20 jobs (MDP 2005).

It is important to view this proposed development against the provisions of the KI Development Plan. The sections of the Plan focused on tourism development and the coastal landscape zone set the context for a development of the type proposed. The Plan states: ‘tourist developments should not be located within areas of conservation value, indigenous cultural value, high landscape quality or significant scenic beauty’ and these ‘should not require substantial modification to the landform, particularly in visually prominent locations’ and when ‘outside townships should … not result in the clearance of valuable native vegetation’ (KI Development Plan 2009: 59). The site selected for SOL was situated in the Coastal Landscape Zone which specifies non-complying tourism development would exceed 25 ‘tourist accommodation units’ and be within 100 metres of the high-tide mark. The SOL proposal stayed just within the limits of these provisions. However, with seven staff accommodation facilities included in the plan, debate on whether the proposal was compliant was inevitable.

It is also important to note the results of a 2004 resident survey entitled ‘mapping the future of Kangaroo Island’ by Brown & Hale (2005) which found:

When asked about developing visitor accommodation ‘in a limited number of coastal strategic locations provided they are attractively situated, small to medium scale, and achieve excellence in environmental design and management’, about 62 percent of respondents believe this is a good idea while 33 percent believe it is a bad idea. Given the highly favourable wording of this question toward coastal development, it is significant that one-third of residents still oppose any future tourism development in the coastal zones. Any tourism development in the coastal zone, even if supported by the majority of KI residents, will likely meet significant opposition (emphasis added, Brown & Hale 2005: 3).

Brown and Hale also found that just over half of respondents ‘expressed low or very low confidence with the development review process to approve development projects in the island’s best interest’ (2005: 3). These observations foreshadowed the contentious climate that would engulf the SOL development proposal.

The Planning Approval Process

Baillie Lodges planned to submit a development application to the Kangaroo Island Council’s Development Assessment Panel by the end of 2004 (‘Luxury lodge for south coast’ 2004:1–2). Baillie did a preliminary presentation to Council at the Ozone Hotel in Kingscote. When asked how his presentation was received, Baillie replied:

There were certainly questions … I think Council then was possibly stacked with people that didn’t really understand this type of development or were perhaps scared that it was going to be something vastly different; a lot of people thought it was going to be a terrible thing like Hamilton Island on KI. They didn’t really understand what a wilderness lodge is or could be. Also I think we were probably perceived to be outsiders as well. I do remember a couple of councillors there were certainly quite openly against the development (James Baillie pers. comm. 29 May 2009).

One of the Councillors, Bill Richards, indicated he was enthusiastic about the proposal but wanted it located in another place such as Vivonne Bay, closer to infrastructure and facilities (pers. comm. 16 May 2009). Richards indicated that the KI Council was divided between those who could be characterised as pro-development and those who were much more cautious about the location and type of development in KI’s natural environment. Although the developers never made a formal application to Council between the end of 2004 and June 2005, the development was hotly debated by councillors (Craig Wickham pers. comm. 26 May 2009).

Max Pritchard, the architect for the project, engaged Bev Overton of Environmental Realist Consultancy to do a botanical survey of the site in preparation for the development application. Although not asked to do so, Overton pointed out several concerns she had with the proposed site, including whether the development complied with the KI Development Plan when staff accommodation was added. She was also concerned about the increased fragility of the dune system from clearance of native vegetation; bushfire risk; impacts on hooded plovers; spread of weeds and soil-borne fungi; safety; sewerage; water supply; and electricity provision (unpublished report 2 December 2004). She was asked to rewrite sections of her report omitting such comments as those on compliance with the KI Development Plan.[5] She submitted an amended report on 7 January 2005.

In late 2004 Paul Weymouth, Manager of the Policy and Planning Group of SATC, began working closely with Baillie as part of his role of ‘working with industry representatives to assist with their development applications’ (pers. comm. 12 August 2009) or as SATC’s key objectives stated, ‘[to] remove unnecessary barriers to existing and new tourism development’ (SATC n.d.).[6]

Numerous interdepartmental meetings were convened to consider the implications of the development proposal. On 14 February 2005, SATC representatives, including Weymouth, met with representatives of the SA Department for Environment and Heritage (DEH), Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation (DWLBC) and Office for Infrastructure Development (OFID) to consider the compatibility of the proposed development with the KI Development Plan and the KI Biodiversity Plan, focusing on issues such as biodiversity, coast, infrastructure, tourism, crown lands and the required conditions if the development was supported in principle (meeting agenda Tobias Hills, Office of Sustainability, DEH).[7] Up to this point, it appears from these documents that the development proposal might still have proceeded through the KI Council’s planning approval process, and DEH was concerned about being prepared to make a formal representation on the development proposal considering that ‘appeal rights are established by making such a representation’.

Another meeting followed on 21 February at which representatives of these same agencies met, joined by a representative of Department of Transport and Urban Planning (DTUP), to consider these issues in greater detail. An interesting concern that was addressed was that these agencies were engaging with the proponent of the development (at this meeting represented by SATC) outside the formal application process. Disadvantages of this approach included a possible negative perception of bias in favour of the development, while the advantages included ‘resolution and mitigation of issues prior to [the] Development Application [being lodged]’, noting that such informal discussions occur ‘without prejudice to [any] response during formal process’ (notes of meeting, Tobias Hills, Office of Sustainability, DEH, 21 February 2005).[8] One can imagine it would be representatives of DEH who expressed concern about the ‘issue of precedence aris[ing] mainly from concern about pressures on few remaining areas of intact natural habitats’ and asking whether the development proposal complies with the KI Development Plan ‘if ancillary units earmarked for staff housing are added to the number of tourist accommodation units proposed’ (notes of meeting, Tobias Hills, Office of Sustainability, DEH, 21 February 2005). Despite these and other concerns raised in this meeting, the recommendations proposed that:

∑ the proposal be supported in principle on expectations of a net public interest benefit

∑ the proponent be encouraged to proceed with the required investigations to assess and address the issues identified above before proceeding with a formal development application

∑ the proponent be encouraged to pursue a development that could serve as a case study of best practice in ecologically sustainable tourism development

∑ support be given through the provision of information and clarifying agency requirements (notes of meeting, Tobias Hills, Office of Sustainability, DEH, 21 February 2005).

SATC stated at this meeting that it would make a ‘scoping submission to the Native Vegetation Council (NVC) on 7 March 2005’. Extrapolating from these meeting documents, one can see the voicing of agency views and perspectives that are congruent with their agency’s raison d‘etre. While the meeting could have opted to oppose the development, it gave it conditional support instead. Former Democrats Member of Legislative Council (MLC) Sandra Kanck argues that this was due to undue pressure in favour of the development by SATC (pers. comm. 20 May 2009). This is discussed more fully in the analysis which follows.

However, while these events were unfolding, opposition was growing because of the siting of the development in a pristine area of the island. In fact, KI Eco-Action Group was so concerned about rumours of the proposed development that it contacted Democrats MLC Sandra Kanck in late 2003. On 25 June 2004, Kanck asked the government what it knew of the proposed development and whether ‘the minister, or her department, was involved in any negotiations with the developers’. The Minister for Industry, Trade and Regional Development said he would refer the question to the Minister for Urban Development and Planning. This reply was not provided until 8 November 2005, some 17 months later. In this reply it was clear that the SATC was meeting with the developers and other government agencies ‘to assist in realising the development’ (reply to Hon. Sandra Kanck by Hon. P. Holloway, Legislative Council).

By late March 2005, SATC representatives were arguing in an email to the DTUP that because the constraints set by the Native Vegetation Act 1991 would prevent the development proposal from being approved by KI Council, major development status was crucial. Additional arguments for SOL to be declared a major development included: ‘[it] is by far the biggest tourism development in dollar value terms on the Island (not scale); it is of the highest strategic significance to tourism; and it involves a complex set of assessment issues’ (email from David Crinion of SATC to Bronwyn Halliday of DTUP 31 March 2005).[9]

Section 46 of the SA Development Act 1993 (major developments or projects) allows the Minister for Urban Planning and Development to declare a development proposal a major development if ‘he or she believes such a declaration is appropriate or necessary for proper assessment of the proposed development, and where the proposal is considered to be of major economic, social or environmental importance’ (Planning SA n.d.). In an effort to demonstrate the economic significance of the proposal, the SATC commissioned Syneca Consulting to draft a report on the ‘Economic Impact of the Southern Ocean Lodge’ in March 2005, which then became the basis of statistics quoted by SA government ministers. This report calculated the direct and indirect economic effects of the development, including an anticipated $7.65 million a year for Kangaroo Island, $1.15 million a year for mainland SA and some 35.2 full time equivalent (FTE) jobs for KI and 42.1 FTE jobs for SA (Syneca Consulting 2005: 1).

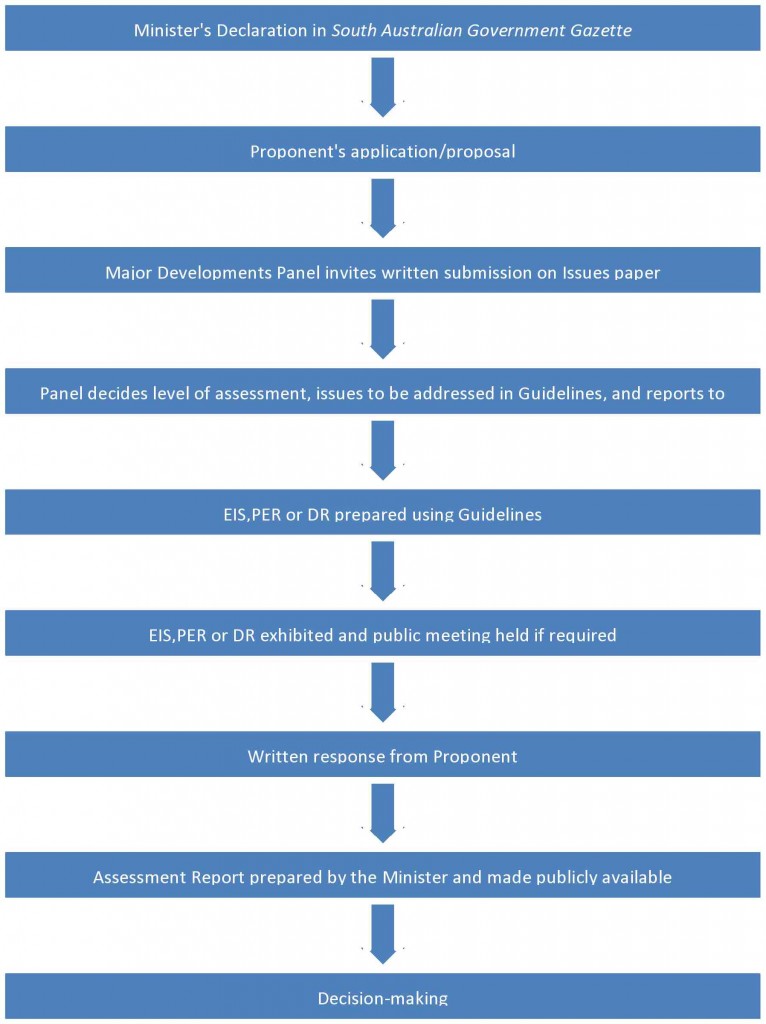

In June 2005, SOL was declared a major development by the Minister for Urban Development and Planning. As a result, the proposal was removed from the local development approval process and placed under the state government’s development approval process under Section 46 of the Development Act. Many in the KI community and on the KI Council felt that this was an unfair denial of their voice (Bill Richards pers. comm. 16 May 2009). The Minister for Urban Development and Planning was asked about the development in the 29 June 2005 Legislative Council and he claimed the proposal was worthy of consideration because it met the criteria of the ‘Responsible Nature-based Tourism Strategy’ co-developed by SATC and DEH, but the major development process would require a ‘rigorous process of environmental assessment’ of the development proposal (Holloway 2005). In fact, frequent mention was made that the sensitive environmental issues associated with the proposed development necessitated the major development process with its potential environmental impact assessment that local council processes do not require ( e.g. ‘Democrats call for KI coastal plan’ 2005). Once the Minister declares a proposal a major development, the development proposal is referred to the independent statutory authority, the Development Assessment Commission (DAC). For a diagram showing the full assessment process for major developments in South Australia, see Appendix A.

The Major Developments Panel (MDP), under Section 46 of the Development Act, released an Issues Paper to inform the public about what it considered to be the significant issues relating to the Southern Ocean Lodge development and to invite public input into the planning process (MDP 2005). The Issues Paper recommended the developers address such issues as: the need for the development; environmental impacts; energy and resource use; waste and pollution; impacts on wilderness values of the region; economic impacts; impacts on communities; management of risks such as bushfires; demands on infrastructure; the effects of construction and operation of the facility; and the compatibility of the proposal with planning and environmental legislation and policies (MDP 2005).

Once the Issues Paper was released on 13 September 2005 the public was invited to contribute written submissions over a four week period on the adequacy of the issues identified by the MDP in the Issues Paper and to raise any other issues of relevance to the development (MDP 2005: 19). Submissions came from government agencies such as SATC, the Department of Trade and Economic Development (DTED), the Coast Protection Board, the NVC and DEH among others. Of these SATC was the only one clearly in favour of the development, while all of the 11 others had queries and concerns. Some 50 submissions were made by the public, the vast majority raising major concerns over the proposal, with seven explicitly against the proposal and only one in favour.

Questions continued about the role of SATC in the planning process and it was clear different agencies of government held differing positions on the proposal. On 11 November 2005 Democrats representative Ian Gilfillan asked the government: ‘The observation that the SATC has sought collaboration and support from other relevant state government agencies to assist in realising this development, does this confirm that the government supports the proposal?’ and the reply given by Paul Holloway included ‘The Hanson Bay development (the proposed Southern Ocean Lodge) is certainly being supported by the Tourism Commission. Other agencies of government, such as DEH, EPA, and others, have their own view in relation to this matter’ (Gilfillan 2005).

Continuing the major developments process, the MDP then used the contents of the Issues Paper and the public submissions to develop a written set of assessment guidelines for the developers, setting the level of assessment required for the proposal. The three possible levels of assessment which can be required by the DAC are:

• an Environmental Impact Statement(EIS) – required for the most complex proposals, where there is a wide range of issues to be investigated in depth

• a Public Environmental Report(PER) – sometimes referred to as a targeted EIS, required where the issues surrounding the proposal need investigation in depth but are narrower in scope and relatively well known

• a Development Report(DR) – the least complex level of assessment, which relies principally on existing information (Planning SA 2007).

In January, 2006, the DAC determined a PER level of assessment was appropriate for the development proposal and released the Guidelines to the proponent setting out what issues the PER assessment should address. The choice of a PER over an EIS assessment process was a major source of controversy in the assessment process as the vast majority of submissions responding to the Issues Paper called for an EIS level of assessment for the proposed development.

Once the level of assessment is established and the Guidelines issued to the developer, the role of the MDP is concluded. The Minister for Planning takes responsibility for completing the process and assessing the proposal under the provisions of the Development Act.

In January, 2006, the KI Council voiced ‘its first protest over the proposed SOL development’ and passed a resolution informing the state government that a PER level of environmental assessment for the proposal was insufficient and a full EIS was necessary (‘Council protest on lodge’ 2006). Planning SA responded that a PER was sufficient because ‘the proposal and its associated activities are relatively “limited in scale” and that a wide range of issues did not require significant investigation” (‘Council slams “cop out” response’ 2006). One of the councillors on KI Council was noted as stating that the ‘State Government had taken the project out of the Council’s hands by declaring it a Major Development’ and that ‘he spoke for a large number of people who were not necessarily against the proposed six-star development, just the site they had chosen’ (‘Council protest on lodge’ 2006). It is ironic that the project was declared to be a major development project to avoid the scrutiny of the local planning process, but was then determined to be sufficiently limited in scale to avoid the rigours of a full EIS process.

The South Coast Action Group (SCAG) drafted a community petition to the Premier and ministers to stop the SOL development because it is ‘inconsistent with the KI Development plan, will destroy pristine wilderness … and will have a deleterious environmental, social and economic impact on KI’.[10] However, this petition was not officially submitted to government, but rather given to the premier’s Chief of Staff because it did not conform to the strict rules on time for petitions to run. Vickery claims one-half of the voting population of KI signed this petition (pers. comm. 15 July 2009). Additionally, Eco-Action and SCAG petitioned the SA Conservation Council, the state peak body for conservation groups, to support their position in opposition to the SOL development in the proposed location, which it did (Fraser Vickery pers. comm. 15 July 2009).

In the run up to the March state elections of 2006, the SA Democrats opposed the SOL development proposal as part of their environmental policy platform. They criticised the role of the SATC in supporting the proposal and urged ‘the government to take appropriate legal action against those who recently destroyed native vegetation to bulldoze a road in[to the SOL] area’ and stated opposition to ‘Government money being spent in support of the project, as proposed by Baillie Lodges’ (SA Democrats 2006).

In April 2006 the proponent of the development released the PER for six weeks of public comment. A public meeting was held at the KI Yacht Club in Kingscote on 19 April to discuss the proposal, the PER and the assessment process. Some 250 people attended. Baillie and representatives of Planning SA and SATC responded to questions from the public. According to Michael Pengilly, Member of Parliament for Finniss (which includes KI),[11] most at the meeting were in favour of the proposal, while attendee Fraser Vickery said some 200 were opposed (Vickery 2006b: 8). Of the some 20 members of the public who spoke during the meeting, only one person spoke out in favour of the proposal: businessman Roger Williams who said that the investment and the planning of SOL made it a proposal worthy of support (Williams pers. comm. 26 May 2009).

At Council meeting on 10 May 2006, KI Council Building Inspector Paul Eames, who was charged with drafting the Council’s submission to the PER process, recommended supporting the development proposal. Instead, a motion was moved that ‘Council not support the proposed major development by SOL in its present proposed location’. This was passed four votes in favour with one vote against (Council minutes 10/5/06). Mayor Jayne Bates castigated the councillors saying it was not a Council decision to make (Black 2006a).

A total of 223 submissions were received from the public on the developer’s PER, with 11 of these from government agencies and the Council. As the developer’s Response Report states:

10 were in full support of the proposal, nine raised issues or made comment on the proposal but were not opposed, 11 were in favour of the proposal if it were in a different location on Kangaroo Island and 193 were opposed to the proposal (SOL 2006).

The government submission from DEH raised at least 47 points for the developer to address, while the NVC, Planning SA and the County Fire Service (CFS) raised issues from their agencies’ viewpoints. KI Council’s submission said it did not support the siting of the development. Supporting the proposal were SATC and DTED. The Member of Parliament, Michael Pengilly, was quoted as saying that the developer’s response document ‘could not be disputed or faulted’ and that ‘sources have revealed that there are State Government Departments that oppose the development for reasons that seem philosophical and not sensible’ (Black 2006b: 3).

In addition to these formal submissions, community attitudes were aired in the Letters to the Editor section of the Islander.[12] For instance, Councillor Scott McDonald, writing to the Islander, commented that ‘the Southern Ocean Lodge development is not only the “thin end of the wedge”; it is a watershed deciding the future of KI’ (McDonald 2006: 4).

Despite this level of community opposition to the proposed development at Hanson Bay and the concerns voiced by key government agencies such as the DEH and the NVC during the PER consultation process, the project was approved by the Governor, subject to conditions, on 19 October 2006 following the recommendation of the Minister in his Assessment Report. The Minister for Urban Development and Planning stated:

This Assessment Report concludes that the Southern Ocean Lodge proposal will have a detrimental environmental impact. However it acknowledges that this impact could be considered acceptable for three reasons:

1. The Native Vegetation Act mandates a Significant Environmental Benefit (SEB) contribution which compensates for the environmental impact

2. The environmental impacts can be minimised through appropriate management and compliance with conditions, and

3. There are economic and social benefits from the project, which are balanced against the environmental impact (Planning SA 2006a: 75)

Discussion

This discussion of this case study will focus on three issues of relevance to general tourism policy, planning and development: the role of SATC in the planning approval process, the use of the major developmentsprocess, and environmental issues.

Role of SATC as Champion of SOL in the Planning Approval Process

As noted earlier, the South Australian Tourism Commission (SATC) played a major role in pushing this development proposal through the planning process. To understand SATC’s role, the context needs to be understood. SA is a state whose economic growth rate is falling behind the national average and which has a particular concern with job creation to retain its young people. The SA Strategic Plan has, as its first objective, ‘growing prosperity’ and seeks ‘high economic growth because it leads to higher rates of job creation and higher living standards’ (Government of SA n.d.). It claims ‘Adelaide has been rated as one of the best places in the world in which to do business, and the challenge for the future is to maintain and improve that position’ (Government of SA n.d.). Securing investment is the key to this strategy. It set a target for ‘performance in the public sector – government decision-making’ to ‘become, by 2010, the best-performing jurisdiction in Australia in timeliness and transparency of decisions which impact the business community’ (Government of SA n.d.). The target for tourism in this strategic plan is to ‘increase visitor expenditure in South Australia tourism industry from $3.7 billion in 2002 to $6.3 billion by 2014’ (Government of SA n.d.).

The role played by the SATC is best understood with reference to its charter and plans, as set out in the South Australian Tourism Commission Act 1993. This Act states: ‘The object of the Act is to establish a statutory corporation to assist in securing economic and social benefits for the people of South Australia through the promotion of South Australia as a tourism destination; and the further development and improvement of the State’s tourism industry’.[13] Accordingly, SATC’s Corporate Plan 2005–2007 mission statement asserts that: ‘SATC develops and promotes the best SA has to offer visitors’ and that it will ‘take the role of navigator, facilitator and at times developer, ensuring iconic product and infrastructure development’ (SATC 2005).

Against this background, SATC emerges as a statutory corporation that is driven by economic indicators and corporate objectives. With its limited budgetary capacities, SATC needed the augmented marketing capacities that the SOL development would give both KI and SA. Such a strategy was key to achieving the monetary targets it set itself of $6.3 billion by 2014.

In its submission to the Major Developments Panel on the Issues Paper in October 2005, SATC’s CEO Bill Spurr argued ‘Southern Ocean Lodge aligns directly with South Australia’s strategic directions for tourism. In particular, the development is consistent with objectives and strategies contained in the: South Australian Tourism Plan 2003–2008, Responsible Nature-Based Tourism Strategy, SA Tourism Export Strategy, Removing the barriers to tourism investment in regional SA’. Additional arguments supporting the proposed development included:

– The development of SOL will send positive signals to investors and could prove a catalyst for further tourism investment in regional SA

– SOL will have a positive impact on consumer perceptions of the State and KI, help strengthen brand, increase marketing critical mass, improve demand levels and improve visitor yield

– SOL is expected to make a considerable and ongoing investment in local staff training (letter 12 October 2005).

For these reasons, Spurr concluded that SOL offered significant economic and social benefits. This was anticipated in the SA Tourism Export Strategy of 2004: ‘Southern Ocean Lodge is a strategic economic development project of critical importance to South Australia’s tourism industry’. In its SA Strategic Plan: Tourism Implementation Action Plan, SATC stated:

This development will be a watershed for SA. It has all the right credentials: consistent with the State’s tourism strategy; respected and proven developer/operator; right environmental ethic; high yield product; will lift brand image; consistent with Development Plan (considered on merit); and has access to finance (which is rare). In light of these extraordinary factors, if this proposal is not approved, the message it will send to the investment community will set the State back considerably in terms of being seen as a place to do business in tourism. This will seriously jeopardize SATC’s capacity to accelerate progress on achieving the target [emphasis added] (SATC 2006: 23).

In another section of this document focused on the ‘critical success factor’ of a ‘positive policy framework’, the SATC specifies a strategy to implement its ‘Sustainable Tourism Package’ which it describes as ‘an aligned series of initiatives to achieve sustainable tourism development’ but it found:

The Native Vegetation Regulations are a major impediment to achieving the target of at least three nature retreat style accommodation developments by 2009 (Source: Responsible Nature based Tourism Strategy). There is no avenue to consider tourism development (except through the Major Development exemption, which is a time consuming and expensive process – and hence disincentive for medium scale development) (SATC 2006: 24).

As will be discussed in the following section, the Native Vegetation Act was created to protect remaining areas of environmental integrity, but here we see the SATC saying that the Act is a barrier to tourism development. It is ironic that SATC claims that sustainable tourism development requires undermining key SA environmental legislation.

With its emphasis on economic imperatives, SATC has also been accused of working against community interests. For instance, the South Coast Action Group (SCAG) of KI responded to this concerted support for the development against what it saw as the KI community interest: ‘it concerns us greatly that the Commission [SATC] shows little regard to the siting of the development, in over-riding the KI Development Plan and compromising the integrity of pristine coastal wilderness on Kangaroo Island – the very thing our visitors enjoy’ (Chris Baxter for SCAG in a submission to the Minister of Urban Development and Planning 15 April 2006).

In the 2006–07 and 2007–08 budget cycles, the SATC allocated $1 million for infrastructure for the SOL (pers. comm. Mark Blyth, SATC, 2008). Some observers objected to this assistance, asking why should the developers be supported when the reason the SOL development proposal was championed was because of the developers’ investment capacity. It could be seen as a case of public funds being used against community (taxpayer) wishes to fund a private developer’s business.

After the opening of the Lodge, Tourism Minister Jane Lomax-Smith was quoted as saying ‘attracting world-class tourism developments such as SOL to South Australia is an important step towards achieving our target of boosting tourist expenditure to $6.3 billion by the end of 2014’ (SATC 2008). She also said ‘The State Government is committed to assisting the growth of the tourism industry, and has worked with SOL developers, Baillie Lodges, to make sure this world-class accommodation … went ahead in the most sustainable way possible’ (SATC 2008).

In contrast, the Democrats Platform Paper of 2006 stated: ‘We are appalled by the role that Tourism SA [SATC] has played in lobbying within government for support for the proposal to go ahead and reject Government secrecy that has been part of the project to date’ (SA Democrats 2006: 12).

Major Development Process: Fast-track for Development?

There are differing views on the use of SA’s major development process for projects such as the SOL. Some see it as a fast track and a rubber stamp, as it can be used to avoid the appeals that the local council process would allow, and it ensures that a development will be appeal-free. However, others argue it involves a more rigorous assessment and is by no means a rubber stamp.

In SA, the major developments process is ‘currently the only trigger for formal environmental impact assessment under our planning laws’ (Mark Parnell, pers. comm. 9 June 2009). However, the concern is that in facilitating development, governments may assert political control to avoid local opposition. Greens member of the SA Legislative Council, Mark Parnell, commented on the SA Development Act: ‘critical parts of the planning system have been used to favour big business with back door access to quick and easy decisions at the expense of local residents, and against the original intent of the Act … “major development” status ha[s] allowed special “fast track” access to favoured developers by the Rann government’ (Parnell 2006). Democrat MLC Sandra Kanck referred to a ‘development at any cost mentality’ evident in the events that unfolded with SOL (press release 30 June 2005). It is pertinent to note that of the 24 projects assessed under the SA Major Developments process since 2003, only one has been refused (Planning SA 2009).

Clearly one of the sources of dissatisfaction with the SOL approval process was the fact that it was not submitted to the local KI Council for local decision making. A former KI Council Mayor and current presiding member of the KI Natural Resources Management Board stated:

My initial reaction [to the SOL development proposal] was disappointment because it didn’t actually go through the planning process here (Janice Kelly pers. comm. 13 May 2009).

In contrast, some interviewees such as former Chair of Tourism KI thought SOL development would be good for KI and moving it to major development status ‘took the emotion out of it’ (Paul Brown pers. comm. 1 June 2009). Another interviewee who served on Council thought that the Council did not have the resources to address such a development application and noted that there was a backlog of applications (Craig Wickham pers. comm. 26 May 2009).

Despite these differing views on the use of the major development process, it is clear from the foregoing discussion that it was partly utilised to avoid the local political tensions. The irony is that the SOL proposal was declared too big for KI Council with its well-articulated plans and TOMM management model derived from extensive community consultations, and yet was sufficiently limited to not require an EIS. Such a situation gives the perception that the development proposal was being facilitated to a successful outcome, rather than being rigorously assessed, in an effort to secure the state government’s targets for tourism.

Environmental Tradeoffs

That the area under development is one of spectacular and rare natural beauty is undisputed. Indeed Baillie noted that when he first investigated the site in 2002 he mistakenly assumed it must be part of the national park ‘I still remember saying to Hayley: wow this would be the most amazing spot for a lodge if it wasn’t national park, because I just assumed that’s where it was’ (James Baillie pers. comm. 29 May 2009). As Bill Haddrill of the DEH described the site:

it was and remains one of the most intact sections of natural environment on Kangaroo Island. The site sits directly between Flinders Chase National Park and Kelly Hills Conservation Park in a fantastic corridor between those areas and one of the most intact sections of the coastline (pers. comm. 25 May 2009).

It was the very quality of this pristine natural habitat that was the issue, as the former Chair of the Native Vegetation Council (NVC) noted: ‘the SOL application advocated clearance in an absolutely pristine area and this was the biggest problem, because the Native Vegetation (NV) Act had no capacity to authorise clearance of pristine native vegetation. That is exactly the vegetation we were set up to protect’ (John Roger pers. comm. 29 May 2009). It was widely recognised that the Baillies had credentials in developing environmentally sensitive resorts but the issue was with their choice of this pristine location.

According to the Acting Executive Officer of the NVC:

The agency and myself, in the role of the Acting Executive Officer, provided consistent advice to the proponents that an application to clear native vegetation lodged under Section 28 of the NV Act would be very difficult for the NVC to approve in recognition that the native vegetation on site would in all likelihood be considered to be ‘intact’ as defined by the NV Act. The Act prevents the NVC from granting consent to the clearance of substantially intact native vegetation. The Native Vegetation Regulations 2003 provide a mechanism for the clearance of intact native vegetation in specific circumstances (Craig Whisson pers. comm. 12 June 2009).

The only way to avoid the prohibition of clearance of intact strata of native vegetation that the NV Act stipulated was to have the proposed development declared a major development so that Regulation 5(1)(c) could be invoked allowing ‘clearance associated with a Major Project’ (Craig Whisson pers. comm. 12 June 2009). Once the development was declared a major development:

The NVC’s official involvement was to provide comment on the PER document prepared consistent with the declaration of the development as a Major Project under Section 48 of the Development Act 1993. The NVC needed to be assured that any clearance of native vegetation for a development approved by the Governor would be: ‘ … undertaken in accordance with a management plan that has been approved by the Council that results in a significant environmental benefit (SEB) … (Craig Whisson pers. comm. 12 June 2009).[14]

Craig Whisson described the process and outcomes regarding the establishment of the SEB in accordance with the provisions of section 21(6) of the NV Act:

The outcome was negotiated between the NVC and the proponent following the site inspection by the NVC and a meeting with the proponent. The SEB involved the protection of the balance of the vegetation on the land owned by the developer being safeguarded under the terms of a Heritage Agreement, and the establishment of a fund to finance conservation projects on Kangaroo Island (pers. comm. 12 June 2009).

The SEB resulted in the establishment of an environment fund called the SOL Development Fund which promised to deliver between $20,000 to $50,000 (partly funded by visitor tariffs) per annum over the life of a ten year agreement for KI environmental projects. A Board made up of representatives of DEH, KI Natural Resources Management, NVC and SOL manages the Fund. According to Tourism Minister Jane Lomax-Smith, ‘the Environment Fund is a great example of the mutually beneficial alliance that can be achieved between tourism and conservation’. Baillie was likewise quoted as stating that the agreement set a ‘new benchmark for public/private collaboration in SA and demonstrates how tourism could benefit conservation’ (‘KI to benefit from Environment Fund’ 2007). This is ironic considering a pristine site was allowed to be cleared and the fund was only developed as a result of the legislative requirements of the NV Act to provide an SEB in exchange for permission to clear. SOL certainly took advantage of the green marketing potential of this fund.[15]

Additionally, it should be noted that it was clear as early as the mid 1990s that ‘ecotourism and nature based tourism pose a number of potential threats to the island’s biodiversity values’ (Lynch 1996). Nonetheless, David Crinion of SATC stated ‘SATC regards SOL to be an excellent model of new private development contributing benefits to the natural environment – a characteristic of eco-tourism. This is consistent with SATC and DEH’s Responsible Nature-based Tourism Strategy. It is particularly important as a model in light of the increasing needs and diminishing public resources for environmental management’ (pers. comm. 9 June 2009, emphasis added).

The DEH found itself in similar circumstances to the NVC, playing its prescribed role in the policy process:

The department certainly provided comments in relation to the likely impact of the clearance of native vegetation required for the construction of the development. Our comments were objective, based on what would be the direct loss of native vegetation and what impact that might have on particularly our threatened species, our flora and fauna and impact on the landscape (Bill Haddrill pers. comm. 25 May 2009).

It is also significant that the development proposal triggered the provisions of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999 as a ‘controlled action’ because it had potential impact on nationally threatened species. However, rather than running its own assessment process, the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage accredited the process of the PER. On 20 December 2006 the development received approval to proceed under the EPBC Act.

Whatever environmental concerns DEH and NVC may have had about SOL, the professional practice of the public service requires a neutral approach in all interactions:

It’s really important to note that whatever the decision made [about the development], the best outcome ongoing into the future is for an organisation such as DEH to work with SOL. You know, once the approval was provided, we could have quite easily turned our backs on it and said ‘We don’t agree’ or ‘We don’t approve of the approvals process – we’re walking away and not having anything to do with it’; far from that. The best thing for us to do is to work with SOL and we continued to work with SOL through the construction phase … that was the change in mindset that we took and that has stood both us and SOL well in continuing to work with them (Bill Haddrill pers. comm. 25 May 2009).

Asked about his views on the significance of the development approval, Former Chair of the NVC John Rogers stated:

When you look at KI as a whole, there is only a relatively small percentage of native vegetation that remains; I believe it is only around ten percent. That is one of the real problems with this part of SA … The level that you need to retain native species habitat for flora and fauna is a minimum of ten percent. So we cannot keep encroaching on pristine areas with this ‘death by a thousand cuts’ and that is what it is; that’s what the NV Act has been set up for. The Act allows for development but it does not allow for further incursion into pristine areas. Because that has already happened; our forefathers already did it and now we are dealing with the remnants (pers. comm. 29 May 2009).

According to ecotourism operator and environmentalist Fraser Vickery, the notion that a developer could economically compensate for such vegetation clearance is unacceptable:

You cannot replace intact stratum that has been cleared by paying money into a fund or revegetating an open paddock, because basically that vegetation [intact stratum] has been untouched pretty much for thousands of years, except for fire and natural processes. So you are actually intervening and destroying something that is priceless; you cannot put a price on pristine habitats on a place like KI (pers. comm. 15 July 2009).

As noted, there were alternative sites available to the developers and opposition would have been greatly reduced if such a site had been selected. As Rogers noted:

There were sites right next door that were [environmentally] degraded to which we [the NVC] would have given total consent. The problem was they wanted to pick a particular plot because it was the most pristine and had the biggest views. But there was a place right next door that had just about the same views though it was degraded and only a matter of kilometres away from where they finally built SOL (John Rogers pers. comm. 29 May 2009).

Assessing the position of bodies such as the DEH and NVC, it is clear that agencies focused on environmental protection are compelled to accept limits to their capacities in a time of tighter budgetary constraints. In the battle to influence policy decisions, their voices carry less weight than those of other public servants in departments focused on trade and tourism in an era when economic logic holds sway.[16]

Analysis

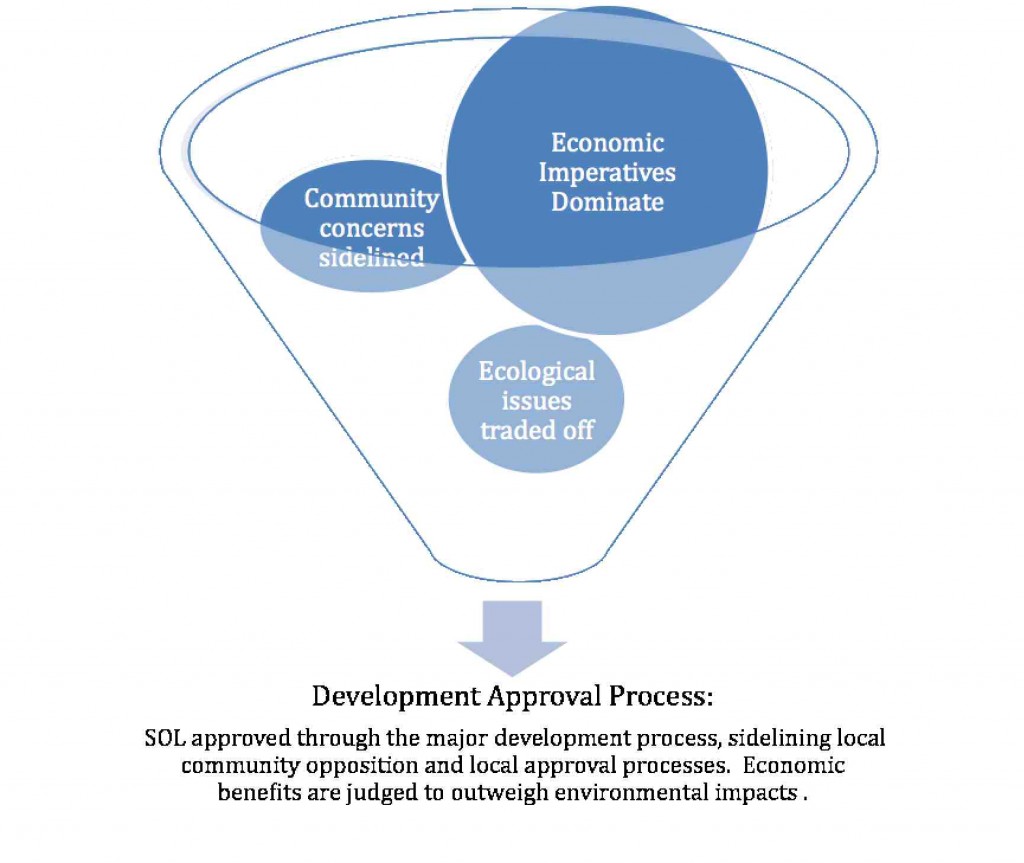

Conventional wisdom is that sustainability is achieved by striking the proper balance between the interdependent systems of society, economy and ecology. Figure 4 models the outcomes of striking this delicate balance with triple-bottom line sustainability resting in the centre of the concentric circles.

Figure 4: A model of interdependent systems: ecology, society and economy. Source: Stilwell (2002: 14)

However, one of the key social constructions of tourism policy in recent decades is the widely held belief that tourism policy is best formed by creating policy environments that empower the private sector and reduce government regulations and obstacles to development. This is a key feature of contemporary neoliberalism. According to Stilwell, neoliberalism’s ‘core belief is that giving freer reign [sic] to market forces will produce more efficient economic outcomes’ (2002: 21). Stilwell claimed that the outcomes of neoliberalism have ‘reoriented’ governments:

The economic activities of government are not reduced, only reoriented towards directly serving the interests of business … The policies certainly create winners and losers whatever their effectiveness in relation to the dynamism of the economy as a whole. (2002: 22)

As a result, the relationship between the market, society and the environment swings out of balance, resulting in an overemphasis on tourism industry priorities and demands for ever-increasing economic growth in the tourism domain.

The outcomes of such an ideology can be seen in the SOL saga. The KI community is clearly concerned about the impacts of economic development on the community and the natural assets of KI, and has committed to years of extensive consultation to create a vision of a shared future through development and tourism planning, and the creation of a world’s best practice tourism management model. Despite this unusually proactive position, TOMM resident surveys have indicated the community shares a scepticism about the community’s ability to influence tourism-related decisions, which can only have been reinforced by the SOL experience.

The SOL development proposal clearly did not align with the KI Development Plan. The KI Council, as the most effective representative of the KI community, was arguably the best agency to assess the proposal under the provisions of the Plan. However, this was subverted by the major developments process.

This path was taken because the NV legislation would have stopped the SOL development. But if ecological sustainability is the goal of sustainable tourism development, then the NV legislation should have blocked the development because, in its proposed location, it cleared a substantial portion of intact, pristine habitat. To comply with the NV Act, the developers could have been pressured to secure an acceptable location that did not result in vegetation clearance. However, rather than follow this path, the major developments process was taken on the advice of the SATC, and thus the provisions of the NV Act were overruled. In one fell swoop, community and environmental interests were overridden.

The role of the SATC as champion of the development was pivotal, as it saw the SOL development as a key for achieving its primary goal of $6.3 million tourist expenditure by 2014. While rhetorically wielding the language of sustainability, the SATC’s actions demonstrated the predominance of economic imperatives in the neoliberal environment of tourism policymaking.

The pro-development bias fostered by neoliberalism is perhaps evident in the fine line followed in the development approval process for SOL, as the government declared SOL sufficiently significant to require major development status, but sufficiently limited to not require the full rigours of an EIS assessment. This sense of a pro-development bias is reinforced by the notion that environmental concerns can be traded in the interest of securing economic goals. As Urban Development and Planning Minister Paul Holloway stated: ‘I acknowledge that the proposed development will have an environmental impact, however on balance this impact is acceptable because of the significant tourism and employment benefits likely to be generated by the resort’ (Planning SA 2006b).[17]

The SOL planning approval process demonstrates that triple-bottom line sustainability will remain an unrealisable ideal while neoliberalism prevails, as the voices of industry with their economic imperatives trump the concerns of local communities and ecological interests. Rather than the ideal balance depicted in Figure 4, the planning approval process demonstrated in this case study reveals a system out of balance, in which economic drivers dominate (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A model showing the dynamics between economic imperatives, community concerns and ecological issues in the development approval process for the SOL.

Conclusion

The tensions between tourism development, environmental conservation and community wellbeing lie at the heart of the tourism policy and planning process. The story of the planning approval process for the SOL development indicates the real obstacles facing local communities such as KI who wish to control development and protect their remaining environmental assets.

Despite having spent the 1990s in extensive community consultations to secure an agreed development plan, a tourism strategy and a world’s best practice tourism management model, the KI community found itself sidelined by the major developments process and its protests going unheeded. Likewise bodies charged with protecting the remaining areas of ecological integrity in SA were clearly pressured in the policy dialogues to accept environmental trade-offs in order to not be marginalised as anti-development ideologues. The disproportionate influence that SATC had in the policy dialogues on the development proposal and the concomitant timidity of the NVC and the DEH illustrate the predominance of business interests over ecological concerns in today’s neoliberal policy environments.

It is clear that, in such circumstances, despite the widespread rhetoric supporting triple-bottom line sustainability, sustainability will remain elusive in the cut and thrust of everyday tourism policy, planning and decision making.

Appendix A

MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS OR PROJECTS – ASSESSMENT PROCESSES AND DECISION MAKING

NOTES:

[1] This is the latest annual report currently available from the TOMM website.

[2] The decline in positive response to this question continued in the 2006/07 period with under 50% stating they feel they can influence tourism related decisions. See: http://www.tomm.info/media/contentresources/docs/Indicator%20Report_Socio%20Cultural%20_InfluenceTourism_Apr07.pdf

[3] The SOL currently offers luxury accommodation with a minimum two night stay starting at $900 per person per night twinshare and $1,350 single. This price includes accommodation, meals, drinks and some touring experiences.

[4] This document was accessed as a result of a Freedom of Information (FOI) request.

[5] Her personal view on the development proposal was that it was a good concept but sited in the wrong place (Bev Overton pers. comm. 26 May 2009).

[6] Weymouth helped Baillie Lodges with ‘case management assistance’ to obtain development approval for SOL. SATC obviously viewed this as instrumental in achieving approval in late 2006 as it stated ‘following SATC case management on behalf of the proponent, the development received approval in 2006’ (SATC 2007b: 28). Baillie stated ‘the government has given it [the development proposal] major development status; it has to go through a process but we have great support, the SA Tourism Commission is very enthusiastic’ (Clifton 2005).

[7] This document was accessed as a result of a Freedom of Information (FOI) request.

[8] This document was accessed as a result of an FOI request.

[9] This document was accessed as a result of an FOI request.

[10] Unpublished petition in author’s possession.

[11] Pengilly was formerly Mayor of KI when the SOL development was first mooted.

[12] Of the some 40 relevant letters to the editor between 2005 and 2008, some 38 expressed significant concerns, one expressed full support and one came from the developer, James Baillie. The one in full support stated: ‘I, unlike others, would like to see development come to Kangaroo Island … do we want our Island to become a retirement village? Not once has a hooded plover ever offered me a job, yet development has. If we keep on opposing every development put forward, eventually developers will not come’ (Boyd 2005: 4). For the developer’s letter to the editor, see Baillie (2005: 16).

[13] http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/sa/consol_act/satca1993432/s3.html

[14] Former Chair of the NVC John Roger addressed this process: ‘Cabinet took the application of the Act away as a requirement; they [the developers] did not need to comply with the Native Vegetation Act. But what they did have to comply with was the environmental impact and we [the NVC] tried to assess that and tried to find a way where the community and the environment would benefit from the clearance’ (pers. comm. 29 May 2009).

[15] While some proponents of the development emphasised that only 1 ha would be cleared for the development, in reality the supporting infrastructure including the staff village, roads, boardwalks and bushfire management requirements meant that the extent of clearance was effectively much greater than the earlier estimate.

[16] Federal Environment Minister Peter Garrett recently gave a speech in Brisbane where he warned that efforts to save some endangered species in Australia may have to be abandoned due to limited funds. See: http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2009/s2659857.htm

[17] Vickery retorted in a letter to the editor that this was absolute nonsense: ‘clearly, the benefit is to Baillie Lodges and not to Kangaroo Island’ (2006a: 4). He also suggested Minister Holloway did not understand the government’s own policy on sustainability.

References:

Baillie, J. 2005. Lodge sustainable and sensitive. The Islander, 6 October, 16.

Black, S. 2006a, Council ‘no’ to Lodge. The Islander, 18 May. Available at: http://kangarooisland.yourguide.com.au/news/local/news/general/council-no-to -lodge/362531.aspx [accessed: 26 May 2009].

Black, S.2006b. Lisa watches Lodge proposal from afar. The Islander, 27July, 3.

Boyd, G.2005. New development brings opportunity. The Islander, 20 October, 4.

Brown, G. and Hale, S. 2005. The future of Kangaroo Island. Available at: http://www.unisanet.unisa.edu.au/Resources/gregbrown/Greg%20Home%20Page/Research/Australia%20(Kangaroo%20Island)/Survey%20Results/Final%20Survey%20Results%20Summary%20(PDF).pdf [accessed: 7 November 2008].

Clifton, C. 2005. A sense of place. Adelaide Matters, 62. [Online] Available at: http://www.southernoceanlodge.com.au/press/AdelaideMattersSept054235.pdf [accessed: 3 March 2009].

‘Council protest on lodge’ 2006. The Islander, 27 January. Available at: http://kangarooisland.yourguide.com.au/news/local/news/general/council-protest-on-lodge/362531.aspx [accessed: 27 May 2009].

‘Council slams ‘cop out’ response’ 2006. The Islander, 16 March. Available at: http://kangarooisland.yourguide.com.au/news/local/news/general/council-slams-cop-out-response/183180.aspx [accessed: 5 June 2009].

‘Democrats call for KI coastal plan’ 2005. The Islander, 27 October , 8.

Duka, T. 2005. Kangaroo Island Tourism Optimisation Management Model Annual Report 2004-2005. Available at: http://www.tomm.info/media/contentresources/docs/2004-2005%20TOMM%20Annual%20Report.pdf [accessed: 4 September 2005].

‘Full steam ahead for $10m ‘Lodge’’ 2005. The Islander, 11 August, 1-2.

Gilfillan, I. 2005, Kangaroo Island Resort, speeches & questions/ environment, 11 November. Available at: http://sa.democrats.org.au/html/print.php?sid=834 [accessed: 19 January 2006].

Government of SA n.d. SA Strategic Plan. Available at: http://saplan.org.au/content/view/96/ [accessed: 20 May 2009].

Holloway, P. 2005. Kangaroo Island Ecotourism. Minutes of Legislative Council, 29 June. Available at: http://www2.parliament.sa.gov.au/hansard_data/2005/LC/WH290605.lc.htm [accessed: 20 May 2009].

Jack, L. n. d. Development and application of the Kangaroo Island TOMM . Available at: http://www.regional.org.au/au/countrytowns/options/jack.htm [accessed: 3 June 2005].

Jack, L. and Duka, T. n.d. Kangaroo Island Tourism Optimization Management Model. Available at: www.sustainabletourism.com.au/pdf_docs/tomm_aug31.pdf [accessed 5 August 2008]/

Kangaroo Island Development Plan 2009. Available at: http://www.planning.sa.gov.au/edp/pdf/KI.PDF [accessed: 5 May 2009].

‘Kangaroo Island to benefit from Environment Fund’ 2007, Media release from Mike Rann, Premier of South Australia, 16 March. Available at: http://www.ministers.sa.gov.au/news.php?id=1381&print=1 [accessed: 4 May 2009].

‘Luxury lodge for south coast’ 2004. The Islander, 19 August,1-2.

Lynch, H. 1996. Kangaroo Island tourism case study. CSIRO Division of Wildlife and Ecology, Canberra. Available at: http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/publications/series/paper9/appnd2_5.html [accessed: 3 March 2009].

Major Developments Panel 2005. Issues Paper: Southern Ocean Lodge, Hanson Bay, Kangaroo Island Proposal. Adelaide, Planning SA, September.

Manuel, M., McElroy, B. & Smith, R. 1996. Tourism. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

McDonald, S. 2006, SOL a watershed decision for island. The Islander, 11 January, 4.

Miller, G. and Twining-Ward, L. 2005. Tourism Optimization Management Model, in Monitoring for a sustainable tourism transition: The challenge of developing and using indicators. Wallingford, UK: CABI, 201-232.

Parnell, Mark 2006. Big business mates given backdoor access to planning system, say Greens. Media release, 19 September . Available at: http://www.markparnell.org.au/mr.php?mr=223 [accessed: 9 June 2009].

Planning SA n. d. Major Development Proposals. Available at: http://www.planning.sa.gov.au/go/major-developments [accessed: 3 October 2008].

Planning SA 2005. Information Sheet: ‘Southern Ocean Lodge’ proposal at Hanson Bay, Kangaroo Island. Government of South Australia.

Planning SA 2006a. Assessment Report for the Public Environmental Report for the SOL. Available at: http://www.planning.sa.gov.au/ [accessed: 3 March 2008].

Planning SA 2006b. Provisional green light for KI tourism development. Available at: http://www.planning.sa.gov.au/go/news/provisional-green-light-for-ki-eco-tourism-development [accessed: 3 March 2008].

Planning SA 2007. Assessment processes for proposals declared major developments and how to have your say. Available at: http://www.planning.sa.gov.au/index.cfm?objectId=B0D6F25D-96B8-CC2B-63BE28584A11F809 [accessed: 1 March 2008].

Planning SA 2009. Previous projects: Major developments. Available at: http://www.planning.sa.gov.au/index.cfm?objectid=BB4948E7-96B8-CC2B-6B2D1A6ED82109B9 [accessed: 29 May 2009].

South Australian Democrats 2006. Goals for the environment: Platform paper 2006 SA Election. Available at: http://sa.democrats.org.au/election/issues/Environment.pdf [accessed: 3 May 2009].

SATC n.d. Tourism Policy and Planning Group. Available at: http://www.tourism.sa.gov.au/about/divisiondetail.asp?id=22 [accessed: 3 May 2009].

SATC 2005. Corporate Plan 2005-2007. Available at: http://www.tourism.sa.gov.au/about/pdf/SATC%20_CorpPlan_2005-7.pdf [accessed: 3 May 2009].

SATC 2006. South Australia’s Strategic Plan: Tourism Implementation Action Plan. Available at: http://www.tourism.sa.gov.au/webfiles/TourismPolicy/South_Australian_Strategic_Plan_230306.pdf [accessed: 3 March 2009].

SATC 2007a. Ecotourism conference win for South Australia, press release, 21 August . Available at: http://www,tourism.sa.gov.au/news/article.asp?NewsID=343 [accessed: 21 May 2009].

SATC 2007b. SATC 2006/07 Annual Report. Available at: http://www.tourism.sa.gov.au/Publications/Ann_Rep_06_07.pdf [accessed 1 March 2008].

SATC 2008. New era for KI tourism, SA Stories E-Newsletter, May.

SOL 2006. SOL Public Environmental Report Response Document. Prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff on behalf of Baillie Lodges.

Stilwell, F. 2002. Political economy: The contest of ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Syneca Consulting 2005. Impact of tourism on Kangaroo Island Council: Final Report . Report prepared for KI Council & SATC.

Vickery, F. 2006a. Lodge conditions a farce. The Islander, 26 October, 4.

Vickery, F. 2006b. Public speaks out over Southern Ocean Lodge. The Islander, 27 April, 8.

Yin, R. K. 1994. Case study research: Design and methods, 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

List of acronyms:

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CFS Country Fire Service

DAC Development Assessment Commission

DEH Department for Environment and Heritage

DTED Department of Trade and Economic Development

DTUP Department of Transport and Urban Planning

DWLBC Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation

EIS Environmental Impact Statement

EPA Environmental Protection Authority

EPBC Act Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act

FOI Freedom of Information

FTE Full time equivalent

KI Kangaroo Island

LAC Limits of Acceptable Change Model

MDP Major Developments Panel

MLC Member of Legislative Council

NV Act Native Vegetation Act

NVC Native Vegetation Council

OFID Office for Infrastructure Development

PER Public Environmental Report

SA South Australia

SATC South Australian Tourism Commission

SCAG South Coast Action Group

SEB Significant environmental benefit

SOL Southern Ocean Lodge

TOMM Tourism Optimisation Management Model

This case study is so well researched and referenced…

The next one, of the similarly unfortunate “Kangaroo Island Pro”, should prove to be as an interesting read too. Kangaroo Islanders are lucky to have this history so well presented.

As you can see, history and documentation will always show the truth to those who seek it, showing the failures – and achievements – of the representatives of Kangaroo Island.

Very upsetting to see the beautiful Island’s ecology abused and ruined.

I had searched a lot of websites for some amazing places like this kangaroo island and found this one most unique and informative..

Great post. Thanks.

It would be great to see some follow up research now that the lodge has been operating for a while, to relook at the impacts.